Any of us in the arts know that criticism stings. Those of us on the recieving end dread reviews; those on the giving end try desperately to put their thoughts into cogent words. But once in a while, you get a review of your own work that, though scathing, can only be giggled at and passed off not as an analysis of your efforts, but rather an insight into the manifold strangeness of the reviewer's complex (and often excerable) soul. My book

Britten and Barber: Their Lives, Their Music was in fact the subject of such a review, and I cannot resist quoting it

en toto. Read on, if you dare, and I take no responsibilty for what follows:

Britten and Barber

Their Lives and Their Music

Daniel Felsenfeld

(Amadeus Press)

The musics composed by Benjamin Britten and Samuel Barber were thought to be somewhat romantic, perhaps a return to the past. Rather than following the lead of such moderns as Stockhausen, Dallapiccola and Olivier Messien, they composed what was thought to be music of and for the people, not unlike the poetry of John Betjeman.

Both lived within that tiny closed, somewhat gay culture of musicians of mid-century America and England. Barber's lifelong lover, Gian-Carlo Menotti, composed opera; Britten's love --- the dandy-ish Peter Pears --- was a noted tenor of the day.

Anyone writing about composers and classical music of the 20th Century has to wrestle with a singular fact that when Barber and Britten were gadding about, Western musical culture was the playground of the rich and the fey, dancing about the once-great metropolitan centers --- London, New York, Boston, Philadelphia, Chicago, San Francisco --- with their opera houses, symphony halls, musicales, and such nearby venues as Tanglewood, Jubilee Hall and Aldeburgh.

At the same time a wholly new music culture was erupting, an iceberg of music-love scarcely noted by the eminent critics of newspapers and magazines of the times. As he discusses these two, two of the most famous musicians of the day, Felsenfeld can quote from reviewers from the pages of The Saturday Review, The New York Times or The Times of London. He can and does cite the words of the movers and the shakers of the day: Leonard Bernstein, Serge Koussevitzky, Eugene Ormandy, Arturo Toscanni.

A radical change was taking place in the world of music just as Barber and Britten were muddling their way through the cultural dustbin. It was the coming of the LP (and, somewhat later, the CD). These created a new world for those of us who refused to put up with the indignities of Culture in the local Symphony Hall: the waiting in line, the expense, the experience of sitting next to someone with terminal apnea (or intractable pulmonary edema), the eternal waiting through that most-forced of pauses --- the pause that oppresses --- the intermission. In "live concert," you and I were forced to wait what seemed like hours to hear what we came to hear.

But there was a new alternative for those of us who loved music as it should be loved. It was to be found in a stereo (or 'hi-fi') system where we could listen to, at the pace we wanted, at the hour we wanted, exquisitely performed music.

Instead of sitting through hours of The Rape of Lucretia, Peter Grimes, Knoxville: Summer of 1915, Anthony and Cleopatria, Serenade for Tenor, Horn and Strings, Sonata for Piano, we could hear, entire, without benefit of comments, coughs, sneezes, yawns or snores, the string quartets of Haydn, the trio sonatas of Telemann, the oratorios of Handel, the chamber music of Dvorák, any of the 211 cantatas of Bach.

We could hear, whole --- without the infernal spell-breaking intermission ---the greatest opera of all time, Verdi's Requiem (we call it opera because that's what it is; just because he was in mourning, the composer was not about to change his form).

We could spend an evening with some of the greatest religious works in western culture: Bach's B Minor Mass, or the St. Matthew's Passion. We could spend an hour or so (drink in hand) hearing that most charming of all set pieces, the vocal version of Stravinski's L'Histoire du Soldat.

At three in the morning, if we so chose, we could turn to the most moving meditation on death ever created, Schubert's 14th String Quartet, Death and the Maiden, named after the anonymous "maiden," the origin of his all-too-fatal disease.

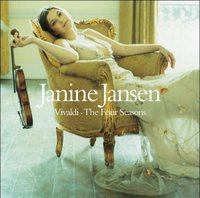

Or, at any hour of the day or night, in any sequence, we could live inside the towering works of d'Aquin, Vivaldi (not the Four Seasons, lord knows), Handel's most obscure oratorios --- Xerxes, Julius Caesar, Theodora, Jephtha --- or any of the great chamber or vocal pieces of Lully, Monteverdi, Rameau, Soler, Purcell.

Thus instead of being dragged to the smart-set Palace of Culture to put up with the likes of Barber and Britten --- or those dead-weights hung on the necklace of western culture (Ferdé Grofe, Delius, Elgar, D'Indy --- or Ravel's blindingly circular "Bolero,") we could be up in the clouds with the masters, never having to hob-nob with the "guardians of culture," those snooty folks who haunted the Met, the Boston Pops, the Philadelphia Symphony, Avery Fisher, etc.

§ § §

Felsenfeld's essay is certainly clearly written, and for scholars who don't have any musical taste, it might even be considered important. For those of us crave worthy music, it will be just another scab off the corpse of Western High Culture. For it is, alas, an essay (with CD!) concerning two neurotic nannies in the masturbatory world of mid-twentieth century music, where audiences would go crazy over something as emotionally stunted as Commando March (for the Army Air Force!) Leonard Bernstein, who played this game for fun as well as for fame and profit, once remarked that Britten's music had "the sound of gears not quite meshing."

The ultimate occurred when we put the disk that came with Britten and Barber into our CD player. The disk spun and spun (and spun). And nothing at all came from the speakers. Not even a whimper. Much less a bang.

--- A. W. Allworthy

(One can just blink--DF)

Addition: If my hot google-searching is at all correct, the above A.W. Allworthy (stagename?) is actually

Reverend A.W. Allworthy, author of the 1976 (sadly out of print) classic

The Petition Against God, published by Mho & Mho works. You may by no means acquire a copy

here.